|

||||

Home | The Diary | Commentary | Credits | Links | Text Files |

||||

|

In July 2000, before I searched my Dad's personal effects, I searched the internet for information about the 31st Infantry Division, also known as the Dixie Division because of its Southern roots. Dad was proud of his service with the Dixie Division. He was fond of saying that it was composed of the Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida National Guard, Suh!

Left: Lou Hall and Marion Hess at the 31st Infantry Division Reunion in Colorado Springs, Colorado, on 24 August 2000. (Paul Webber) I learned from Marion Hess about the 31st Infantry Division reunion on Thursday, 24 August 2000 at the Radisson Inn North in Colorado Springs, Colorado. I attended the reunion and met Marion, a delightful lady who reminded me of my mother. Marion introduced me to Mr. Louis L. 'Lou' Hall, one of "the boys from F Company" who had shared a foxhole with my Dad on Mindanao. Marion described my meeting with Lou as a rare event. Meeting him was a happy surprise. He remembered Dad as a tall skinny guy with curly black hair. Lou is from the small town of Nemaha, in southeast Nebraska near the Missouri River. He said: I did my basic training at Camp Beale, California, and trained as an artilleryman. I landed in Guadalcanal after it was captured, and later joined the 31st Division on the side of a mountain near the Driniumor River in New Guinea. Just like that, I became an infantryman. New Guinea was a hard fight for the 31st.

Lou Hall's weapon was the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). He remembers combat in New Guinea, Morotai, and Mindanao, digging in four-to-a-hole, and pulling guard in two-hour shifts. During the Battle of Colgan Woods on Mindanao, where Chaplain Colgan was killed on 6 May 1945, Lou said that he was one of the men who recovered the padre's body. Later during that battle, he was firing his BAR from a "chevron" position (a description of the shape of the hole) when a Japanese mortar round impacted behind him and blew him out of the hole. Lou said: I still remember flying through the air with my arms out. They put me in a field hospital that was made of tents set up in the kunai grass. He was not seriously injured, and returned to duty. At one point he was also hospitalized with malaria for two weeks. He remembers being with Dad at Malaybalay and in the mountains near Silae. Silae was where the boys of F Company narrowly escaped being killed by Japanese mortar fire. I remember Dad telling me about this episode. He said that the unit moved into a position previously held by the Japanese. Later, the CO had a bad feeling about the position and moved the unit back across a river to another position. Japanese mortar fire fell on the first position early the next morning. Here is the way Lou Hall remembered it: We were on the push north to capture a Japanese airfield near Silae. American dive bombers would bomb and strafe the field by day, but the Japs would fix the holes at night. Then the Jap planes would use the airfield as a jumping off point to bomb our medical and supply rear echelons. F Company reached Silae and had dug in on the top of a hill for the night, when the CO realized, 'This isn't a good place to be.' Just before dark, Lieutenant Powell moved us across a creek and had us dig into the top of another hill. At dawn the next morning, Japanese 75-mm mortar fire plastered the other site. Their mortars were behind a hill, and they couldn't depress the angle of the tubes enough to hit us.

Through Marion Hess, I also

discovered Dr Thomas M. Deas of Homer, Louisiana. Dr Deas has

written of his World War II experiences as Regimental Surgeon of the

124th Medical Detachment.

Until 2006, he met every year with the surviving medics of the 124th

Infantry Regiment from the Pacific campaign. I attended Tom's WWII

Medics Reunion at the Wilson World Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee on 6

October 2001, and took the photo at lower right. It shows Dr Tom

Deas, his daughter Peggy Godfrey, and his grandson David Cook, just

after Tom completed a local television interview.

My Regimental Medical Detachment was composed of 120 enlisted men, 8 MDs and 2 dentists. Later they cut 3 MDs out and we had just 5 assigned docs. Usually we had 4 docs and about 85-90 enlisted because of casualties. Most of the time the Captain assgned to HQ as the Asst Regimental Surgeon was down in the Battalions. Most of the time we did glorified first aid and tried to get casualties back to the rear to keep us from slowing down our advance. My medics stayed with the soldiers, at least stayed up with them. My HQ medics were always right behind the lead battalion. We treated and evacuated as fast as possible. It worked very well in the PI as we could get the most critical patients back fairly rapidly. In New Guinea, I held patients in my arms at night, knowing they were going to die because we couldnt use lights and had to move when our troops moved. We were right in the middle of 15,000 Japanese Troops. It was H---. But we did carry some for 3-4 days. Used AntiTank Company to be litter bearers. Took 8-10 men per litter. I don't remember ever being afraid except sometimes in the jungle at night when those darn snipers shot about every two minutes. The bullets would hit a tree and ricochet with a 'spling.' I cant praise my medics enough. I had a number KIA [killed in action] about 30-40 WIA [wounded in action] and lost some to age. Paul, I could talk about those boys all night long. That is the reason we still meet. We are a family. Right now we are down to about 20 plus or minus that we have been able to keep in contact. We meet in October. I am 'The Old Man'. In 2002 Dr Deas sent me comments that he prepared for his Medics Reunion in Starkville, Mississippi that year. They echo what is written above. He titled the document To My Medics at our Reunion 2002.

In April 2004 Tom Deas wrote:

Above: The Battle of Colgan Woods by Jackson Walker. This painting depicts Chaplain Colgan braving Japanese gunfire to come to the aid wounded medic Robert Lee Evans. Evans and Colgan were both killed. (This hangs in the 124th Infantry Regiment museum in Orlando, Florida; photo provided by Marion Hess, October 2000.) In October 2003 Tom Deas referred to this photo and told me: It didn't look like that. The trees were all stripped bare of leaves from all the firing. We never did clear the Japanese from those woods until our artillery arrived to help. In October 2005 Herb Thurston, one of Tom Deas' medics, told me: We medics didn't wear the Red Cross brassard on our sleeves, because it was a target for the Japanese. The artist added the brassard in the painting to identify the medic who is shown giving aid to Evans. In 1992 Dr Deas wrote a series of three articles for the Guardian-Journal newspaper of Homer, Louisiana, entitled From Olden Times: A Day in the Life of a Regimental Surgeon. This is the story of his combat experiences on Mindanao on 5 and 6 May 1945, just prior to the Battle of Colgan Woods. Tom sent me copies, and I have transcribed them here: Deas 1, Deas 2, Deas 3. He also wrote Last Full Measure, the story of PFC Hugh Summerfield, one of his medics who was killed in action during the Battle of Colgan Woods. Marion Hess wrote: Did you know that Tom had a medic who gave up a stripe to get into the 124th Med. Detachment? Name was Sgt. Slagel. He was in and out of the Army and ended up the only medic who served in three wars. They had to mold a badge just for him. He died last year [1999] and the Army named a mess hall at Ft. Sam Houston in Texas after him.

I was sad to learn that Marion Hess died on 29 August 2001. On 12 August 2001 she wrote: I am still around, BUT you won't believe my story. I came in the hospital last Mon. for dehydration, etc. Was doing well and was to go home Thurs. On Thurs. 4:30 a.m. I proceeded to go into my bathroom after the nurse had finished her thing 20 min. before. I proceeded in and unbeknownst to me she had spilled water on the tile floor. One step in and I went skiing. Lucky me!!! I broke my ankle in 3 places and now scheduled to stay here in rehab as once before for a couple weeks. I would not let them do surgery and opted for a cast. I was afraid my bones are so soft from the drugs that they would not hold the screws and I am afraid of infection. I heard the bone crack in the same place as 1981 in the previous break. The break is nasty but set well. Just a matter of time now. Then she suffered a stroke. Tom Deas wrote: Paul, Marion Hess had a massive stroke a few days ago and died last night at about 10 PM, Aug 29, 2001. I'll miss her.

Paul Tillery was the Regimental Motor Sergeant with Service Company, 124th Infantry Regiment, and has written a history of the 124th Infantry Regiment in World War II. It is a detailed account of the rigors of infantry basic training, and a history of the regiment's campaigns on New Guinea, Morotai, and Mindanao. He also wrote the poem Service Company, for the first Service Company reunion in 1983. Both provide valuable insights. I contacted Paul Tillery in October 2000 and he wrote: My thought is to make known the terrible conditions under which our foot soldiers had to fight in the SW Pacific and especially at the Driniumor River in New Guinea. I think it's a story that needs to be told. The Driniumor River is east of Aitape on the north coast of New Guinea. On 18 August 1944 the headline of the Southwest Pacific NEWSMAP was: Aitape Defeat Wrecks Jap 18th Army. The 3rd Battalion, 124th Infantry Regiment, under the command of Lt Col George Dent 'Pappy' Williams, was awarded Battle Honors and a Presidential Unit Citation for outstanding performance of duty in action near Aitape, during the period 12 July 1944 to 7 August 1944. Read Dr Tom Deas' personal account of a Japanese Beach Attack, and his piece entitled Those Eyes, in which he recalls the horror and exhaustion of the Driniumor River Defense in July-August 1944. In August 2001, Dr Deas revisited his Memories of Combat at the Driniumor River.

Read other veterans' accounts of combat at the Driniumor River by Mac McCracken and Bill Garbo. Bill Garbo was a member of the 26th Quartermaster War Dog Platoon, and served with both the 124th Infantry Regiment and the 112th Cavalry Regiment. I learned more of his experiences in a telephone interview with Bill Garbo on 2 February 2002. Delbert Parris was in B Company, 1st Battalion, 124th Infantry Regiment, and was wounded by friendly fire at the Driniumor River on 8 August 1944. I learned of Mr. Parris through his son, and called him on 21 March 2002. He remembers combat on New Guinea, Morotai, and Mindanao. Delbert Parris said: We had been fighting near the Driniumor River for 19 days. The Japanese had just about quit attacking, and our CO said we were going back to the beach. We got to the beach and dug our perimeter. The next morning we got out our K-rations for breakfast. Those K-ration boxes burned good, and we used them to make cooking fires to heat the rations. I think that an artillery spotter from the 32d Division spotted the smoke from our cooking fires, and called in artillery on us." (Read more.) The K-ration was packaged in an outer cardboard box and an inner wax-coated box which burned quite well. For in-depth accounts of the battle, see Defending the Driniumor: Covering Force Operations in New Guinea, 1944 by Dr Edward J. Drea, Aitape by Marion Hess, and HyperWar: New Guinea.

Archie Peers was in F Company, 124th Infantry Regiment, and wrote the poem The Men of the One-Two-Four. I called him in Krum, Texas, in June 2001. He is 79 years old, a retired postmaster, and is active in the Elks organization. He does not remember my father, but when I mentioned my Dad's diary, he hurried to get his own and read a passage he had written about the casualities in F Company during the Battle of Colgan Woods. He was in the 4th platoon (the heavy weapons platoon) and still writes to his former platoon leader, Albert Francis Magone of Monongahela, Pennsylvania, whom he described as "a pure Italian." Archie said that he was a runner. He explained: On Mindanao in 1945, we were on the offensive, and the Japanese were on the defensive. Our company would send out patrols, and the Japanese would wait in ambush. The guy on point usually "got it." There were lots of casualities. As a runner, I was sent back by Captain Goodman [F Company Commander] and Lt. Magone to get a machine gun squad, plus whatever they wanted from the mortar section, and bring it up to their position. In March 2002 Archie Peers wrote: On our last patrol before the war's end, three other grunts and I carried a badly wounded soldier back along the trail to a field hospital (three tents with surgeons and emergency whatever) through no man's land. We were instructed by the Regimental doctor not to give him water due I imagine to his heavy dose of morphine. We left the C.P. about 9 pm and found the tents along the trail around 3 am. Some Captain told me to grab a blanket from the pile and lie down. About that time they opened the flap on the tent and brought the litter out, covered with a blanket. We had carried in a dead man and I never knew who he was or the three others with me as litter bearers. The trail was rough and to this day I consider it the toughest night of my nearly eighty years.

Archie Peers told me about another F Company soldier, Frank Savant. I

called Frank in Iowa, Louisiana, on 25 January 2002. He was in the

3rd platoon of F Company with my Dad and Lou Hall. He remembers my

Dad as a quiet guy who didn't have much to say. Frank said that he

had enlisted at a young age, and was with the 124th Infantry Regiment

since its activation at Camp Blanding, Florida, in November 1940. He

remembers the New Guinea campaign, the Battle of Colgan Woods, and

combat in the mountains near Silae. He said that the unit lost as

many men to tropical diseases as to the Japanese. He recalled 1st

Sergeant Jack Silverthorn who got "black malaria" and died on

Mindanao.

Right: Robert Buchanan (front left) and his buddies in F Company, 124th Infantry Regiment. (Robert Guy Buchanan of Albertville, Alabama, through his daughter Jo Ann Poe) Frank Savant said: He [Jack Silverthorn] turned black and died in 3 days. It was rough going on Mindanao. We lost a lot of people, more than on New Guinea. I have a photo of the men of F Company that was taken at the end of the war. Only 27 of the original 217 men were left. He also talked about the native Moro people of Mindanao: They weren't the friendliest people. You had to be careful around them, but we got along OK and some of the Moros scouted for the company. They didn't like you fooling with their women - didn't even like you to look at them. One day I had to go on a patrol across a river, and we ran into the Little People. They were very short, wore only G-strings, and carried bows and arrows. The Moros stayed away from them - wouldn't even cross the river with the patrol, because they knew it was their land. In February 2002 Frank Savant wrote: I do remember your dad. I was the NCO who picked them [the new replacements] up at the Battalion Headquarters and escorted them to the front. I was probably the NCO who carried the submachine gun. All platoon Sgts carried one. But I was not the one who shot the Jap. I also was very upset about that and raised hell about it. We were told to shut up and forget it. Placid Stuckenschneider, OSB, was a member of the 34th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division during World War II. He wrote The Last Campaign: Mindanao, a revealing account of the foot soldier's life in jungle combat on Mindanao in 1945. (Dad's friend John Branz also served in the 24th Infantry Division on Mindanao.) Brother Placid sent me a copy of his story and wrote: My story is from one PFC's point of view - from a foxhole.

Dr Tom Deas told me about a friend, Jimmy Mize, with whom he had played college football at Louisiana Tech. Tom and Jimmy met at the airport in Shreveport, Louisiana in 1946. Tom wrote: I was in Shreveport at the airport and saw a very good friend with whom I played college football in l935. He was watching those old C-47s, which were used by the airlines for passenger planes in 1946, and I also was watching them. I said, 'Jimmy, I love that old C-47! That thing used to feed me in the service.' He said, 'I used to drive one of them and I love them too.' We talked a little and I found that he was the pilot that dropped our rations and supplies to us down in New Guinea! He told me that he had lots of trouble flying over those New Guinea mountains because of the air currents. I always thought the C-47 was probably the most important plane in the Pacific. I called Mr. Jim Mize in Ruston, Louisiana, on 30 January 2002, and he shared some memories. Beginning in June 1943, he flew with the 433rd Troop Carrier Group out of Port Moresby, New Guinea. In July-August 1944 he dropped supplies to units fighting at the Driniumor River near Aitape. The planes were affectionately known as Biscuit Bombers, and the troops loved them. Mr. Mize said: We flew north out of Port Moresby over the Owen Stanley Mountains to support operations near Buna and Lae. Later we dropped food and ammunition for the troops fighting near Aitape. We had to hug the ground a lot because the clouds were stuffed with rocks! We made our drops from 300 feet. In New Guinea many Japanese troops were surrounded, bypassed, and left to starve. If an aircraft went down near them, it was bad. The Japanese were unmerciful. After Manila was recaptured we were based at Clark Field, and flew many liberated POWs from Manila to Tacloban, Leyte. I witnessed so many Army, Navy, and Seabees during the war. They were great men. From June 1943 until August 1945, I logged more than 3800 hours, most of it over water." (Read more.) Mr. Robert Hyde flew C-47s with the 317th Troop Carrier Group in New Guinea and the Philippines. The 317th was known as the Jungle Skippers. Bob wrote: I was particularly interested in the account of Mr. Mize. I also flew from California to Nadzab, New Guinea. I followed just about the same route. Then north through Mindanao, Luzon, with side trips to China, Korea, and even Japan.

Dad mentioned the different types of landing craft on which he sailed in the Philippines. These were shallow-draft, flat-bottom boats of various sizes, that were designed to land men and materiel on the beaches. The lack of a keel enabled them to run up on the beach, but made the ride rougher at sea. Mr. Bill Martin was the Executive Officer, and then Commanding Officer of LCI(L)-637 in New Guinea and the Philippines during World War II. I called Bill in Aztec, New Mexico, on 22 March 2002, and he talked about his service in 1944-1945. He was last stationed at Subic Bay in the Philippines, and spent eight months transporting mail and people between Subic Bay and Manila. He said: On our first trip to Manila there was a horrible smell in the air. I investigated and found an old walled city by the harbor. One of the buildings was a jail, and it's roof was gone. Inside were two large cells filled with decomposing bodies. Apparently the Japanese had locked these prisoners in the jail and left them to starve. The British had an aircraft carrier in the area which transported liberated British POWs from the Japanese prison camps on Formosa to Manila. My boat transported some of the former POWs from the carrier to shore. They were walking skeletons. (Read more.)

Troop trains were used for cross-country troop movements during World War II. These trains were pulled by steam-powered locomotives, coal-fired machines that generated a lot of soot. Tom Deas wrote of his troop train travels during 1942-1944. He said of one train: It was a coal-burning cinder tosser. My collar, neck, and clothes were filthy. Dad probably rode the Missouri Pacific Railroad to Little Rock, Arkansas in December 1944, on his way to basic training at Camp Robinson. I have wondered about the route he took in April 1945 between St. Louis and Fort Ord, California. I contacted Mr. Don Snoddy of the Union Pacific Railroad, and he wrote: Troop train routes were never published. I've talked to vets who were on them, and who knew railroads, and they criss-crossed the country sometimes rather than taking the most direct route. If he had taken the passenger train route, he would have gone to Kansas City then on the Santa Fe to Los Angeles. His other option was on the Missouri Pacific to Dallas and then on the Southern Pacific to California. I asked whether he might have traveled to Fort Ord via Denver and Salt Lake City. Mr. Snoddy replied: The route you suggest is quite probable. Except he wouldn't have gone through Denver; he would have gone through Pueblo. It's the route of the Royal Gorge, the train that goes through the Rockies not around them. It would be a straight shot on the Missouri Pacific, Denver and Rio Grande, and Western Pacific railroads. On this route, he would have started the journey in St. Louis, and traveled through Kansas City, Pueblo, Cañon City, the Royal Gorge, Grand Junction, and Salt Lake City, before arriving in Oakland; but as Mr. Snoddy noted, it is unlikely that he took such a direct route. Mr. Verne White, a veteran of the 503d Parachute Regimental Combat Team, said: The troop train was a boring experience. We had to be moved in a somewhat confusing fashion in order to mislead the enemy spies as to our final destination. Oh yes there were spies from the Axis powers, Germany, Italy, Japan, and even some U. S. citizens who disagreed with the participation of the nation in the war. Consequently we were routed in other than a direct route to San Francisco. Read another account of troop train travel by Mr. Tom Higley. Also read the story of the North Platte Canteen. This is where the citizens of North Platte, Nebraska, fed more than six million GIs on the troop trains that stopped at the Union Pacific Railroad's Bailey Yard during World War II.

Dad was drafted on 28 November 1944, and was inducted into the U.S. Army at Fort Sheridan, Illinois. He sent this postcard to his parents on 1 December 1944, before being transferred to Camp Joseph T. Robinson near Little Rock, Arkansas, for infantry basic training. This camp was named in 1937 for U.S. Senator Joseph Taylor Robinson, the Senate majority leader during FDR's first presidential term. During World War II, Camp Robinson was expanded to 48,188 acres and was used for basic training and to house German POWs. During basic training Dad qualified as sharpshooter with his primary weapon, the M1 Garand rifle. The M1 used an en bloc clip that held 8 staggered rounds. The clip and rounds were inserted into the magazine as a unit, and the clip was ejected upward after the last round was fired. Dad told me about loading and firing the M1: You used your thumb to push the 8 round clip into the top of the rifle. If you weren't quick enough, your thumb got smashed by the bolt as it snapped forward. You had to hold the rifle firmly against your shoulder and cheek, or the recoil would beat you up. He also told me about firing a machine gun downrange, and watching the tracer bullets to adjust aim; he fired expert with the .30 Cal Air-Cooled Light Machine Gun. During one long hike he became dehydrated and exhausted, and had to be returned to the rear. I remember him saying: The Army picked the most miserable swamp land, good for nothing else, and made it a basic training camp. Infantry Basic was rigorous. Mr. James E. Mahony of Lorain, Ohio, said this of Camp Robinson: Camp Robinson, Little Rock, Arkansas. There was an infantry training camp where I stayed until September [1942]. At that time, I had quite an experience, as life became 'full speed ahead.' They gave us all the things and all kinds of courses to get us in the proper condition and training. There were obstacle courses, and things of that nature. It was quite strenuous and the temperature was quite high. We would take long hikes, and we'd also participate in parades...So, it was quite strenuous. According to Mr. William Joel Blass, Camp Robinson was a ...replacement training center ...where we taught them rifle marksmanship. We taught them what we called dirty fighting, which I taught for a long time; knife and bayonet fighting, basic map reading, booby traps. Read more about the history of Camp Robinson and Senator Joe Robinson.

I recognized the Priest immediately. He is my Great Uncle, Father Ambrose Branz. My Mom believes Dad was visiting him, perhaps in Arkansas. Notice that Dad and John were not wearing their rifle marksmanship badges, so they were still in basic training at the time of this visit. Sister Magdalen Stanton at Saint Scholastica Monastery in Fort Smith, Arkansas, confirms that this is Subiaco Abbey in Subiaco, Arkansas. It is located in the Arkansas River Valley between Little Rock and Fort Smith. In February 2004 I sent Sister Magdalen a copy of the photo of John Branz shaking hands with his uncle, Fr. Ambrose Branz. She replied: The building photographed is on the Subiaco Abbey campus, Subiaco, Arkansas, which is approximately 50 miles directly east of Fort Smith. There have been many additions and the flora is quite luxurious now, so the campus looks different. Sister Magdalen also confirmed through a friend at Subiaco Abbey that Fr. Branz left Subiaco to help found a new Benedictine priory in Corpus Christi, Texas, and later died in Texas. The Corpus Christi priory was moved to Sandia, Texas in 1975, and closed in 2002. Notes:

Whenever we were on patrol and heard enemy gunfire, everyone would hit the dirt and fire back in the direction of the gunfire. The 2d Battalion, 124th Infantry, was awarded Battle Honors and a Presidential Unit Citation for extraordinary heroism in military operations against an armed enemy, during the period 22 April 1945 through 27 June 1945. Marine Air Group 24 (MAG-24) was based at Titcomb Field, Malabang, in April 1945, and provided close air support for Mindanao ground operations. These air support operations were directed by Support Aircraft Party 30 (SAP 30) of the U.S. Army Air Corps. Captain Martin M. Rudich wrote a summary report on the activities of SAP 30, which gives insight into the 31st Division's operations on Mindanao. It documents that air attack was often used instead of artillery because of difficult terrain conditions, and describes the weather on Mindanao on 3-15 June 1945 as "abominable." Tom Deas confirms that the jungle was thick, the roads were mud, and most bridges were destroyed by the retreating Japanese. Here is an excerpt from The Southern Philippines, 27 February - 4 July 1945 by Stephen J. Lofgren for the U.S. Army Center of Military History: On 30 June General Eichelberger [8th Army Commander] reported to General MacArthur that 'organized' Japanese resistance had ended. But as the Japanese did not fully share that view, small unit mopping up operations continued for some time. Throughout Mindanao, pockets of Japanese troops, safeguarded by the impenetrable terrain of the island's unexplored jungle expanses, survived until the end of the war, when some 22,000 emerged to surrender. More than 10,000 Japanese died in combat, while 8,000 or more died from starvation or disease during the campaign. From 17 April to 15 August 1945, 820 U.S. soldiers were killed in eastern Mindanao and 2,880 were wounded. The Philippines had been liberated.

There were many tropical disease hazards in the Pacific. I remember Dad talking about having to take atabrine to prevent malaria. Prior to the introduction of atabrine, malaria was epidemic among troops in the Pacific Theater. The drug was not well-liked because it was bitter and turned the skin yellow; and it didn't always work. Dad said that on 6 August 1945, the day the first atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima, he lay ill in a field hospital with malaria. Dad also spoke about how F Company 1st Sergeant Jack Silverthorn died of malaria. At age 25, this man was already an "old man" to the younger troops. Dr Tom Deas wrote: People sometimes stopped their atabrine to get home. I took two tablets a day and never had any problem, except GI upset sometimes. I remember writing a poem to The Diarrhea. I had it on occasions and thought I was going to die!! Dad told me about one hospitalized soldier who had shot himself in the foot. This self-inflicted wound (SIW) was intended to buy a ride home. This was a high price to pay, as an M1 round causes a large exit wound. Soldiers, sailors, and airmen were used up during World War II. If they recovered from an illness or injury, they were sent right back into combat. The Real War, 1939-1945 and Victory at Sea, published by The Atlantic magazine, are revealing articles. Dad's older brother, Roy Webber, flew B-24s and B-17s in the 487th Bomb Group of the 8th Air Force during World War II. He survived 34 combat missions over Europe. Roy said: You had to fly until you were dead or they thought they could replace you.

The second atomic bomb was dropped on

Nagasaki

on 9 August 1945. Read about the

Decision

to Drop the Atomic Bomb at the Truman Library. For more information,

see Hiroshima: Was It Necessary?

On 2 September 1945

Japan

formally surrendered. Here is the

Surrender

Document. If Japan had not surrendered, the Allies were prepared

to launch Operation Downfall, the invasion of the Japanese

homeland. The 31st Infantry Division was scheduled to be part of

the second phase of the invasion, Operation Coronet, and

probably would have fought elements of the Japanese 12th Army

Right: Map of proposed Operation Downfall. (USMA) After the war ended, Dad did not have enough "points" to come home immediately. On 10 May 1945, two days after VE Day, the War Department announced the Army Point System, which assigned points to service members based on their length of duty, whether they had served at home or abroad, their combat records, and their family status. Each service member received an Adjusted Service Rating Card to tally the points. 85 points were required for discharge and, in theory, those with the highest scores would be brought home first. In practice, many service members in critical military specialties had their discharges delayed.

The 31st Infantry Division returned home by Christmas 1945. Units

which remained in the Philippines after the war became part of

AFWESPAC, an administrative command with headquarters in Manila. The

8th Army

Area Command passed to the control of AFWESPAC on 25 August 1945.

After the war, Dad and Lou Hall were reassigned to the 506th Engineer

Light Ponton Company on Mindanao. They stayed on Mindanao for another

year. When I met Lou Hall in August 2000, he spoke about playing

volleyball with the boys of F Company before they were broken up and

reassigned. He also reminisced about pulling bridge guard duty. This

consisted of guarding a bridge check point, awaiting surrendering

Right: Japanese soldiers surrendering near the Pulangi River at Valencia, Mindanao, in September 1945. (George Young)

Lou Hall said that the 506th Engineer Company was located "up on a

hill near Cagayan, on Cagayan Bay." This was

Cagayan de

Oro, on Macajalar Bay. Lou told me that he had prior experience

with heavy equipment. When he was a boy, his father "ran a blade"

(ran a bulldozer) for the Nebraska Highway Department. When another

soldier was transferred home, Lou was promoted to Tec 4 and assigned

to supervise the dozers and heavy equipment of the 506th motor pool.

Right: The tractor named Death Trap. It was supported by only two large drive wheels and the pin which connected it to a trailer. Lou Hall said that operators of this vehicle paid particular attention to that connecting pin, because if it failed the tractor would pitch forward and kill the operator. (Lou Hall)

Lou Hall said that one of the first things he did was use a dozer to clear an area of jungle for a baseball field and a basketball court. He said that they also set up a place to wrestle. He remembers that Dad didn't wrestle, and that Dad said, "You guys are too tough." Lou also described how he built latrines: I took a dozer and dug a trench. Then I knocked one end off of a 50 gallon drum, set it in the trench, and filled in around it. On top of this I put a piece of wood with a flapper seat. We put up a small tent for privacy. Once in a while we removed the top, dumped gasoline over the mess, and burned it to help control the smell. One time a guy named Parmele [Nelson C. Parmele Jr] poured the whole five gallon can of gas into the barrel. That was too much. When he lit it the flames shot up fifty feet!

Lou Hall remembers the loading of ships at the dock in Macajalar

Bay. He used tractors to haul equipment to the docks, and recalled

that Filipinos worked the docks, while U.S. personnel worked the

lines aboard ship. He said that the Americans sent much equipment by

ship to Pusan, Korea. He also spoke of having to detonate surplus

dynamite in a remote canyon, to prevent it from being stolen by

Filipinos. He shipped out of Manila aboard the U.S. Army Transport

Sea Barb and arrived in San Francisco Harbor on 11 August

1946. Lou was diagnosed with leukemia in 1995 and had a recurrence

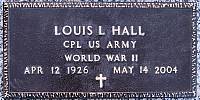

of the disease in April 2004. He died on 14 May 2004. On 21 May 2004

Louis

L. Hall was buried at

Right: Lou Hall's grave marker on 24 November 2004. (Paul Webber)

Docks at Bugo where we loaded Heavy

Dad had a friend named Tec 5 Edward Zabrusky, Army Serial Number 37713618, whose name is in his address book. I have a roster of the 506th Engineer Light Ponton Company which shows that after the war, Ed Zabrusky was assigned to the 506th, along with Dad and Lou Hall. Then he was reassigned to Headquarters Company, Base K, AG/RC, in Tacloban, Leyte. I found two typewritten letters that Eddy Zabrusky wrote from Leyte to Dad on Mindanao in 1946: Zabrusky 1, Zabrusky 2. The letters reflect a friendly person who enjoyed tennis and playing the piano. They include comments about several mutual friends. I did an internet search for "Edward Zabrusky," and found a reference to the Annual Zabrusky Lecture at Michigan State University in East Lansing, Michigan. I wrote to the university in August 2000 and received a reply from Terry Denbow, Vice President for University Relations. He told me that I indeed had the "right" Ed. MSU's Ed Zabrusky was the same Eddy Zabrusky who had befriended Dad on Mindanao. Before moving to Michigan State University, he was a reporter for the Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph (now The Gazette). He joined the MSU News Bureau (later called Media Communications) in 1956, and became its director in 1962. He retired in 1994. Terry Denbow wrote: He attained legend status here because he was not only a pro, but an extremely kind and thoughtful man.

I learned from Terry Denbow that Ed Zabrusky had two surviving sisters, Dorothy and Betty Zabrusky. In October 2000 they lived in Colorado Springs only a few miles from my home. We met and I learned that Ed Zabrusky never married. He died at Penrose Hospital in Colorado Springs on 24 July 1998, and is buried at Lakeside Cemetery in Cañon City, Colorado. The Zabrusky Family is from Cañon City. There were five girls and three boys. When I met them Dorothy and Betty were the only survivors. George G. Frye was a mutual friend of Dad and Ed Zabrusky. I called George on 8 April 2002, and he recalled being transferred from the 31st Infantry Division to the 506th Engineer Light Ponton Company after the Japanese capitulation. He remembers my Dad as being tall and skinny, with blue eyes. George said: The 506th Engineer Depot was on a big bluff near Cagayan de Oro. There were two miles of winding road from the top of the bluff down to the beach and the town. Bob and I were both Catholic; we used to get a jeep and go to the Catholic Church in Cagayan on Sundays. There is a high bluff about one mile south of Macajalar Bay that rises to 400 meters above sea level. This is probably where the 506th Light Ponton Company was located in 1945-1946.

Local transportation in Cagayan - Bob After the war, Dad was assigned to at least four different units on Mindanao. The first of these was the 506th Engineer Light Ponton Company. In May 1946, he was with the 686th Quartermaster Bakery Company; in June 1946, he was with A Company, 311th Engineer Construction Battalion; and at the end of his tour he served with Headquarters and Service Company of the 311th Engineer Construction Battalion. He attended the Adjutant General Administrative Clerical School, Class #8, and graduated on 27 July 1946, with "demonstrated proficiency" in Military Occupation Specialty Number 405 (Clerk Typist). The commandant of the school, LTC Wallace V. Eslinger, wrote him a letter of commendation which said, in part: I am taking this oppotunity to commend you upon the splendid record you attained while a student at this school. The exceptional level you consistently maintained was the result of individual initiative, hard work and sincere effort. You have excelled in your academic work and your conduct has been exemplary. It was about this time, perhaps during the clerk typist course, that he typed a History of the 506th Engineer Light Ponton Company. I remember Dad showing me this document in 1968 when I was taking a summer school typing course in high school. I retyped a portion of his original document for practice. During my search, I found both documents saved together in his dresser drawer.

Morale was high in the Philippines after the war. The troops were 8000 miles from home, but nobody was shooting at them. Accidents and venereal disease were the biggest threats. Mom told me that Dad spoke of the common practice of Filipino farmers offering their daughters to GIs. Marion Hess told me that Fred Hess spoke of having the time of his life working with dozers and other heavy equipment. In Eddy Zabrusky's typewritten letter to Dad on 5 May 1946, he wrote (in all-capital letters): SO YOU AND THE SEA URCHINS DON'T SEEM TO GET ALONG? WELL HERE THEY HAVE JELLYFISH TO CONTEND WITH. CRABTREE BRUSHED UP AGAINST ONE WHILE SWIMMING AND IT LEFT NUMEROUS OPEN SORES ALL OVER HIS LEGS. THAT IS ONE REASON WHY I DON'T LIKE TO SWIM AROUND HERE. The next paragraph begins: WHAT IN HECK ARE YOU AND FORD AND WECKY [Weckman] TRYING TO DO? YOU KNOW A FELLOW COULD GET HURT IN ONE OF THOSE VEHICLES. Dad spoke to me about his encounter with the sea urchins while swimming. This was probably in the waters of Macajalar Bay. He also told me, and my Mom confirmed, that once he was riding in the back of a truck which was involved in an accident. He took some splinters in the scrotum from the bed of the truck.

Dad finished his Army enlistment with the rank of Tec 5, with Headquarters and Service (H & S) Company, 311th Engineer Construction Battalion on Mindanao. His Army discharge certificate confirms that he departed the Pacific Theater on 14 September 1946 and arrived in the States on 30 September 1946; It also states, "RECOMMENDED FOR FURTHER MILITARY TRAINING," but Dad decided not to stay. Tec 5 Robert T. Webber was honorably discharged from the U.S. Army at the Separation Center, Fort Sheridan, Illinois, on 29 November 1946. Among his things I found photos of the U.S. Army Transport General O. H. Ernst with this caption: |

||||

|

||||

|

Stamped on the back of each photo is this notation:

STRAND PHOTOS Dad must have bought these photos after disembarking in San Francisco. Left photo: Alcatraz Island is at far left, and the ship has a slight list to port. Right photo: The ship's port side deck is swarming with GIs returning from the Pacific Theater. Dorothy Zabrusky, a nurse, saw this photo and exclaimed: No wonder they all got sick! Dorothy told me that her brother Ed Zabrusky contracted malaria during the war, and had relapses after returning home. Helen Branz, the widow of John Branz, told me that John also had malaria, and returned home ill and very thin. John returned home soon after the war because of his father's sudden, unexpected death.

I sent Dad's photos of the General Ernst to NavSource Online. They are posted here:

USS

General Oswald H. Ernst (AP-133) Yves Hubert sent me a photo of an earlier arrival of the General Ernst in San Francisco Harbor, when it was operated by the US Navy as the USS General Oswald H. Ernst (AP-133). On 7 June 2007 Mr. Thomas J. Mulhern of Waco, Texas found Dad's diary website. He wrote: I was just browsing the web when I ran across your your father's story and found that old "AFWESPAC" patch I hadn't seen for over 55 years. I read further and found the pictures of the General Ernst which had carried me from Manila to San Fransisco, California. What memories. Did your Dad mention the ship's sound system playing the recording of "Beyond The Blue Horizon" every morning and evening of that trip? Brings tears to my eyes every time I hear that number. I was there in Luzon, mostly in Manila and Quezon City for about a year, and never in combat. In fact I enjoyed most of that time over there. I was a T/5 in an Ordanance Company when discharged in 1946. I recollect that there was a horrific typhoon a short time before we loaded for the trip to the dock [in Manila]. You were right on the sale of the pictures. When we debarked at San Francisco, they were waiting there for us. I bought 2 for about $10 which at that time was 1/5th of my month's pay. Thank you and may God bless you and yours,

Many GIs brought home souvenirs from World War II. Dad brought home a Japanese Arisaka Model 38 rifle. The photo at right confirms that his souvenir was the 38-inch carbine version of the Arisaka 38 (not the 50-inch standard Japanese infantry issue, or the intermediate 44-inch version). This was the type of rifle used against him on Mindanao. He didn't speak about how he got it, but I remember him showing it to me when I was about 12 years old. He demonstrated the bolt action mechanism, and showed me how to stabilize a rifle for firing. He wrapped his left forearm in the sling to assure a firm grip and stockweld. He let me examine the weapon and I remember many details. The wooden stock was dark brown and weathered, and the sling was intact. The rifle bore was relatively small (consistent with a calibre of 6.5 mm). The bolt handle was straight, and protruded through an opening in the curved metal dust cover. The dust cover slid on tracks on each side of the receiver, and moved with the bolt. The action was stiff, but it still worked, and there was very little rust. The round button-like safety at the rear of the bolt assembly could be turned with the heel of the hand. There was an adjustable rear sight ladder which flipped up for long distance aiming. I remember the 16-petal chrysanthemum stamped into the top of the breech. This symbol indicated that the weapon belonged to the Japanese Emperor. Here are photos of an Arisaka Model 38 Carbine and the Model 38 breech and bolt. The chrysanthemum stamp is visible on the breech, in front of the closed dust cover. (Read more about the Arisaka Model 38 rifle.) At that time the rifle was a curiosity, and I had no thoughts about how it had been used. I never saw Dad fire it, but Mom did. She told me that he was home from college during the Christmas break of 1948. She was visiting him at his father's house in East St. Louis on New Year's Eve, and he brought the rifle out on the front lawn. He fired one round into the air at midnight. My sister Laura told me that, with the permission of Dad and her 7th grade teacher, she once took the rifle to school for "show and tell." Times were different then. The rifle was stolen during a burglary in 1976.

Dad attended Cornell University using the Albert C. Murphy Chemical Engineering Scholarship, which he earned for academic achievement at East Saint Louis High School in 1944. Cornell held the scholarship for him until he returned from his Army service, but decreased his $1200-per-year scholarship by the amount he received from the GI Bill. Here is an excerpt from the letter which Dad received from Edward K. Graham, Office of the Secretary, Cornell University, dated 5 June 1944: I merely have in mind Federal aid that might, together wtih a full payment of the Murphy award, give you a lot more than you needed... All I am thinking of is a Federal scholarship plan for veterans that might duplicate, in part, the work of your Murphy Scholarship. Dad earned the Albert C. Murphy scholarship by academic achievement. He earned his GI Bill benefits by serving in combat during the war. He deserved the full amount of the Murphy scholarship. Mom agreed. In 2004 she said: They took away the amount of the GI Bill from the Murphy Scholarship. We really could have used that money, because we were penniless. We were scraping bottom. Bob had a summer job, but it wasn't enough. We borrowed $50 from his parents, and $50 from my mother; and we took out a $250 loan from the college, with interest. We started out in the hole, but we made it. Bob graduated, had his diploma, and got a good job with Monsanto. His starting salary was about $360 a month. We paid back our parents first, and then the school. Mom said that Dad arrived at Cornell two weeks after classes had begun, and had to catch up. He took 19 credit hours each semester for ten semesters to earn his Bachelor of Science degree in Chemical Engineering in 1951. It was a tough curriculum, but much better than being in combat. He initially shared a house with four other students. He worked hard, but like most college students, he had some juvenile moments. I remember Dad telling me how he and his roommates used to light farts. Mom confirmed that one roommate named Red had a lot of gas, and provided the raw material for these experiments.

Dad had a fine singing voice, which he developed by singing in the Saint Elizabeth Church Choir. Like his mother Irene, he loved to sing harmony. One of his favorite songs was Adeste Fideles (O Come All Ye Faithful), sung in Latin. At Cornell he joined the Tau Chapter House of Alpha Chi Sigma, a professional chemistry fraternity, and had time for some fraternity fun. In 1997 (five years after his heart attack) he showed me his fraternity song book, entitled Houseparty Hymnal. As I began reading aloud the lyrics to the song Souse Family on page 9, he launched into song: Drink Drink Drink Drink, I am sure that Dad also enjoyed singing the Cornell Alma Mater on page 3 of the songbook. My sisters Laura and Rita later became Dad's fraternity brothers when they joined the Beta Delta Chapter of Alpha Chi Sigma at the University of Missouri-Rolla (now Missouri University of Science and Technology).

My mother and father met in East St. Louis during the Summer of 1947. Mom said that their parents' houses were in the same block, but they did not meet until they were introduced by Johnny Branz. They were married by Monsignor Peter Engel at St. Elizabeth Church on 6 September 1949. Johnny Branz was the best man. They raised eight children; I came along the year Dad graduated from Cornell. He worked for the Monsanto Company for almost thirty five years, and became the Director of Engineering for Monsanto's Agricultural Products Company before retiring in 1985. He was a good provider. Dad loved the outdoors and camping, even after being in combat. The Army taught him how to eat on the run, and he in turn taught us. During our first cross-country camping trip in 1960, we drove all day and into the night before stopping at Red Rock Canyon State Park near Hinton, Oklahoma on Route 66 (now Interstate 40). We were all very hungry. Before pitching the tent, Dad opened cans of cold corned beef hash for supper. It was the best meal I ever ate! Dad liked to cook camping meals for us on the Coleman propane stove. He called his favorite recipe Chef's Delight, leftovers mixed together and cooked in a skillet. It is good that we kids were not picky eaters. He taught us how to G.I. a picnic table, that is, clean it. He also taught us police call, that is, how to line up abreast and walk through a campsite to pick up litter when we broke camp. Dad taught us to leave a campsite cleaner than we found it. During the long drive to a campground, sometimes Dad would lead the family in song, a tradition he learned from his mother Irene. One of his favorite driving songs was I've Been Working On The Railroad. Dad enjoyed singing the harmony to this song. He fulfilled his dream of becoming a pilot by taking flying lessons at the St. Louis Flying Club at Lambert Field. Mom said that he and his friend Dale Arrant made a pact to complete flight training together, or pay for the other's training. She also said: I never saw Bob so high as when he came back from a flying lesson. He was exhilarated. He wouldn't drink beer for days ahead of time, so he would have a clear head for flying.

I remember this period and have reviewed Dad's flight log. His first flight was on 8 June 1963, and he received his private pilot license on 29 November 1963. He trained in the Piper PA22 Colt, a single-engine, two-seat, tricycle-gear airplane, which had stubby high wings and looked to me like it shouldn't be able to fly. After he earned his license I remember many preflight visits to the National Weather Service at Lambert Field, and many local and cross country flights in the Cessna Models 150 and 172. My favorite part of flying with Dad was the takeoff. As the wheels left the ground, much of the vibration vanished and I was amazed to see the ground receding, while wondering, "What is holding us up here?" I also remember listening to the repeating Morse code signature of the St. Louis (STL) nondirectional beacon (NDB), over the droning of the aircraft engine: dit-dit-dit dah dit-dah-dit-dit (13 wpm) It was comforting to hear this rhythmic code and know that we were close to home. Dad was a good pilot, and I had complete trust in his abilities. His primary lessons to me were: Don't stall at low altitude, and don't fly in bad weather. As the demands of family and job grew, there was less time for flying. Dad last flew as Pilot in Command on 4 February 1967. He logged a total of 146 hours of flight time. The KØMED on his headstone was his Amateur Radio call sign. When Dad was a boy, his Uncle Bill Sculley sparked his interest in radio by building an oatmeal box crystal radio set for him. Mom told me that Dad began his Amateur Radio hobby after he took an electronics course at Cornell University. He earned his FCC General Class license with call sign K9AZO in the Summer of 1951, after he moved the family from Ithaca, New York to East St. Louis, Illinois. When we moved to St. Louis in 1957, his call sign changed to KØMED. Dad had an intuitive sense of radio. He knew it by heart. I remember him stringing dipole antennas, sometimes while perched precariously on the roof. As my brother Tom and I grew, Dad taught us Morse code and helped us earn the Amateur Radio General Class license. We were pressed into service to help rig a forty foot tower for a yagi antenna, and to climb trees to adjust dipole antennas. I will never forget helping Dad build a 2-kilowatt linear amplifier in the basement while he smoked cigars. His handle on the air was Bob (Baker Oboe Baker). Dad loved the hobby, I think because he loved being in contact with the world, not being "...cut off from the rest of the world so completely." I can still hear him calling: CQ 40, CQ 40, CQ 40 meter phone. This is K-Zero-M-E-D, Kilowatt Zero Mike Easy Dog, Kilowatt Zero Mexico England Denmark, calling and standing by... 73, Dad.

Paul Michael Webber, MD |

||||

Home | The Diary | Commentary | Credits | Links | Text Files |

||||

|

||||

Left: Master Sergeant Aubrey (Paul) Tillery in 1943. Right:

Paul Tillery in 1989. (Paul Tillery)

Left: Master Sergeant Aubrey (Paul) Tillery in 1943. Right:

Paul Tillery in 1989. (Paul Tillery)

Left: A steam-powered locomotive pulling a train. Right: Union

Station in St. Louis, Missouri.

Left: A steam-powered locomotive pulling a train. Right: Union

Station in St. Louis, Missouri.

Left: The Combat Infantryman Badge. In the words of Tom Deas, Dad was

a foot slogger, an infantry rifleman. He arrived on Mindanao

after the worst of the fighting was over, and was involved in the

dangerous mopping up operations. It was his unit's job to

search out and destroy the Japanese who were fleeing eastward from

Silae toward the Agusan Valley in northeast Mindanao. Dad told me

that he never saw the Japanese soldiers who shot at him, but he

recalled the unmistakable sounds of artillery and mortar rounds

flying overhead, and rifle rounds ricocheting in the trees. He said:

Left: The Combat Infantryman Badge. In the words of Tom Deas, Dad was

a foot slogger, an infantry rifleman. He arrived on Mindanao

after the worst of the fighting was over, and was involved in the

dangerous mopping up operations. It was his unit's job to

search out and destroy the Japanese who were fleeing eastward from

Silae toward the Agusan Valley in northeast Mindanao. Dad told me

that he never saw the Japanese soldiers who shot at him, but he

recalled the unmistakable sounds of artillery and mortar rounds

flying overhead, and rifle rounds ricocheting in the trees. He said:

Left: Unit patch of U.S. Army Forces Western Pacific (AFWESPAC). This

patch is on the left shoulder of the Eisenhower Army jacket

that Dad wore home in 1946.

Left: Unit patch of U.S. Army Forces Western Pacific (AFWESPAC). This

patch is on the left shoulder of the Eisenhower Army jacket

that Dad wore home in 1946.

Left: Edward J. Zabrusky. (Michigan State University)

Left: Edward J. Zabrusky. (Michigan State University)

Left: A Piper PA22 Colt at Colorado Springs Airport on 17 May

2003. (Paul Webber)

Left: A Piper PA22 Colt at Colorado Springs Airport on 17 May

2003. (Paul Webber)